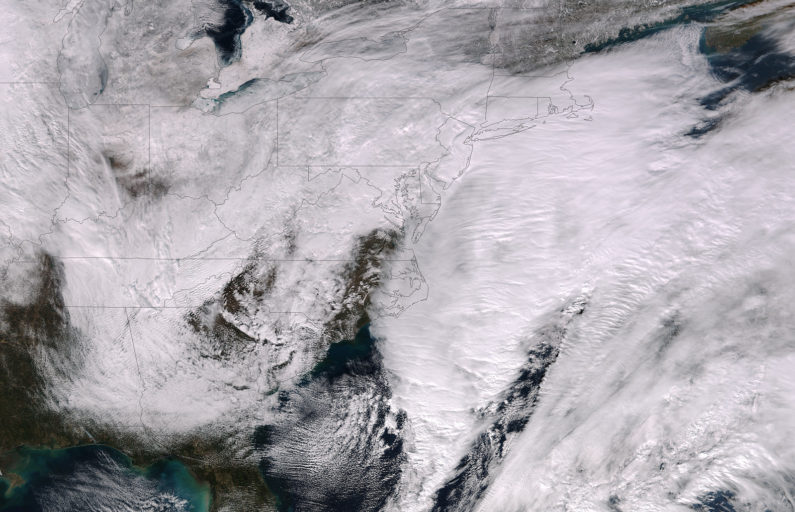

In the aftermath of a winter storm that mercilessly slammed DC to NYC this past weekend, severe weather is on the minds and lawns of many Americans this winter. Mother nature can be an unforgiving force in all regions and seasons: whether she manifests as a sizzling drought or blizzard of the ages, humans are left to scramble for safety with emergency supplies and stockpiles of canned goods. Too often, severe weather events lead to injuries, deaths, and costly damages to property and infrastructure.

Living on a planet with a weather cycle and plate tectonics comes with its inherent risks, and that’s not to mention the severe weather events that climate instability could result in. Regardless of cause, humanity is lucky in the sense that we’re better able to predict, prepare, and stay safe under dangerous conditions. This is largely due to the advancement of weather, disaster relief, and rescue technology.

Extreme weather and other natural disasters can now be detected early on, meaning you’re unlikely to have a typhoon sneak up on you reading Kafka on the beach. It’s thanks to technology that this early and accurate forecasting is possible: for decades, doppler radar, observation tools and computer calculations have been utilized to generate weather predictions. The improvement of these tools along with the addition of weather satellites has upped the accuracy of forecasting over time.

The improvement of forecast technology has been instrumental in the implementation of weather alerts and other types of notifications that help people prepare for harsh weather. Tools like the American Red Cross’ DigiDoc send mass alerts to people in affected areas; most of smartphone owners in the US have built-in alerts that warn of flash floods and other weather-related dangers. Sometimes these may seem superfluous — if it’s raining hard, you probably don’t need a text to tell you — but if the weather event is something like a tornado, these alerts can save lives.

There’s also new technology that allows people to stay connected and safe both during and after severe weather events. Facebook recently released a tool called “Safety Check” that lets people in disaster-affected areas check-in to let their friends know they are safe. But technology goes beyond even this — survivors can alert emergency responders with their mobile phones, sometimes even without Internet connection, for example, through mesh networks like the Serval Project. There are also many emergency and survival apps that work with or without wifi and cell service.

For those in need of emergency relief, rescue and assistance has improved tremendously over the years as well. From drone supply deliveries to rescue robots and radar search tools, individuals at risk can be located, supplied, and ultimately rescued from unsafe areas — whether from flooded homes or piles of rubble.

It’s a relief to know that through the blizzards of today and the quakes of tomorrow, the probability of safety and survival is greater thanks to intelligent minds and effective technology. While we’ve no way yet to change or control the weather all together, the ability to detect danger and avoid harm is a bright spot in a stormy sky, capable of saving millions of lives (and dollars) each year.

Featured Image: NASA GSFC via Flickr.